It's Not Just Masculinity That Can Be Toxic

Is it time to ditch the terms “masculinity” and “femininity” altogether?

In the last few years, the Western world has been on quite a rollercoaster when it comes to our judgements of masculinity.

Hollywood reigniting the #MeToo movement about seven years ago prompted a lot of talk about toxic masculinity. Diversity, Equity and Inclusion (DEI) initiatives mushroomed across industries, with the aim of rightly accelerating women’s emancipation and safety in the corporate world. Long gone are those days.

Many men (even those unimplicated in any form of violence) eventually took the toxic masculinity narrative as a personal attack rather than an attack on the system, which in fairness it sometimes was. I even detected my 13-year-old son carrying feelings of guilt and starting to push back against them, which I wrote about in Fortune. And so men launched a backlash en masse, backed by a growing number of anti-feminist, far-right influencers and populist governments around the world supported by disinformation-spewing social media algorithms.

Now we are at a point where braggadocio-type masculinity is back in fashion, with its emphasis on physical strength, dominance and emotional detachment, alongside its corresponding trad wife-type femininity that emphasises physical beauty, demure manners and homemaking.

I have long been interested in the asymmetry in the way our societies label masculinity and femininity and whether I can quantify any lopsidedness. Moreover, I have been asking myself why there has been such a great emphasis on toxic masculinity but not on toxic femininity.

After all, if the definition of toxic masculinity is assertiveness and power that have metastasised into aggression and abusive force, then the corresponding definition of toxic femininity would be care and cooperation that have metastasised into martyrdom and self-destroyed personal boundaries.

Every time we lose ourselves in someone else’s needs to the point of over-exhaustion and/or resentment, we have fallen prey to toxic femininity. But we do not label it that way… and maybe that is a good thing. Conversely, perhaps we have been frivolous in our use of the term “toxic masculinity”, which has come at a cost.

AKAS’ research reveals that historically, the general public, academic scholars and journalists have all been significantly more preoccupied with masculinity and its derivative term toxic masculinity than with femininity and toxic femininity. This isn’t surprising given that women have been relegated to the sidelines of society for most of time. For example, our analysis of Google, Google News and Google Scholar search results shows that the term “masculinity” appears 6.6 times more frequently than the term “femininity” in Google News, almost twice as frequently in academic papers and 1.7 times more frequently in general Google searches. However, interestingly, masculinity is more likely to have been used in a negative context than femininity in news media, academia and general public use. Once we add the adjective “toxic” before “masculinity” or “femininity”, the use of the term “masculinity” proliferates: in academic papers “toxic masculinity” has been used an astounding 53 times more frequently than the term “toxic femininity”, and respectively 33 and 14 times more frequently in general Google searches and in Google News.

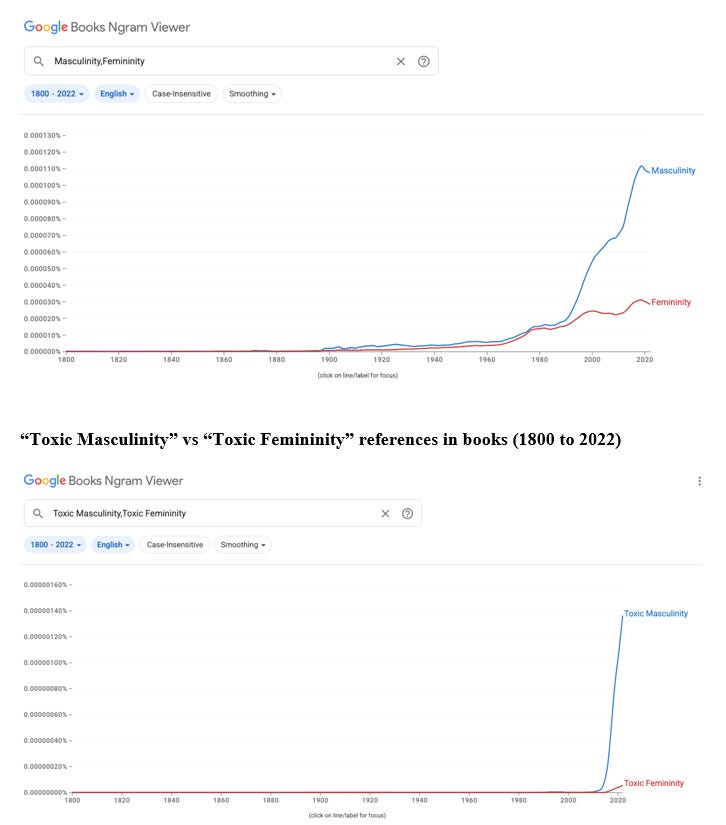

According to Google Books Ngram viewer research, between 1800 and the 1990 the terms “masculinity” and “femininity” were used in similar proportions of books, but sometime during the 1990s, use of the term “masculinity” exploded (see image below). Then around 2018, as the #MeToo movement gained pace, a similar uplift occurred in the use of the term “toxic masculinity”. It shot up almost vertically for a few short years (see Image below). Seeing this data exposing the negative narrative surrounding masculinity makes it easier to appreciate how a significant number of teenage boys and men may have felt in the negative sportlight.

“Masculinity” vs. “Femininity” references in books (1800 to 2022)

Toxic femininity may have been in focus much less than toxic masculinity because of its limited destructive power. Toxic femininity results in self-harm, while toxic masculinity results in harming others. Toxic femininity hurts the person displaying it, typically but not necessarily a woman. By contrast, toxic masculinity has the potential to hurt many more than the person displaying it.

We know from homicide and sexual violence statistics that men are more likely to display toxic masculinity i.e. to be overly aggressive and to use destructive physical coercion. However, while toxic femininity and masculinity are more likely to skew towards each of the two dominant genders, anyone, regardless of their gender, could display either or even both. I therefore ask myself: how helpful is it to slap an identity label on a term that captures a pattern of behaviour that has been inherited from many previous generations? And a term that requires a clarifying answer to the question “what does this mean?” before it is fully understood.

Why not call these behaviours what they are - aggression and self-aggression, for example? Or abuse and self-abuse?

Like Ruth Whippman, author of “BoyMom: Reimagining Boyhood in the Age of Impossible Masculinity”, I would argue that the label “masculinity” is not helpful. Whippman argues that the term “masculinity” has been overused and carries connotations of oppression, particularly in the context of the asymmetry that exists in comparison to the term “femininity”. Indeed, AKAS research shows that the phrase “celebrate femininity” generates 30 times higher returns in Google search than the phrase “celebrate masculinity”.

For Whippman, the solution to a healthy masculinity does not lie in introducing a “positive masculinity” framework because the word “masculinity” is inherently tarnished. Instead, she sees the answer in ditching the model of masculinity altogether.

“…when it comes to truly shifting cultural norms for the next generation of boys and allowing them to embrace their full humanity without shame, we might do better to ditch the masculinity rhetoric altogether. Because rather than challenging the old stereotypes and patterns, the whole positive masculinity framework actually seems to be reinforcing them”,

she concludes.

The word “femininity” is not without its problems either. Those on the right use it in a very narrow sense to express a woman and her body being of service to family-making and others, while those on the left despise it for its limiting stereotypical connotations. My personal thinking on the use of the word has evolved significantly over the years. When I wrote the first Missing Perspectives of Women in News report in 2019 I encountered some condescension from feminist scholars for quoting authors like Shor, who had defined cooperation and harmony as “feminine values” and consensual human-centric management as “feminine style”. The feminist scholars in question were arguing that this label led to a reductionist worldview which hurt the equaliy argument by stopping it from being embraced by all. I wasn’t convinced but responded to the critique by prefacing any statements of this nature with the phrase “traditionally seen as feminine” in subsequent work.

The penny dropped for me one day over lunch in a conversation with my son. I was arguing that the world, and boys in particular, needed to step more readily into their feminine qualities like empathy, collaboration and emotional expressiveness when he asked me the following question:

“Do you think that you will ever be able to convince a boy to focus on anything if you define it as ‘feminine’?”

This simple pragmatic question stopped me in my tracks and led to a substantive shift in my thinking. I realised then how restrictive and stifling the terms “femininity” and “masculinity” are in a world that has dumped so many harsh judgements and stereotypes onto each of them.

I have now repivoted my values, identity and parenting away from the heavy and increasingly politically-charged labels of “femininity” and “masculinity” more towards humanity. For me this means seeking a balance between compassion and competitiveness, emotions and rational thoughts, contemplative softness and drive to achieve, the body and the mind, being and doing, giving and recieving, listening and asserting.

These days I spend much more time thinking about the kind of humans I would like my children and I to be than about how masculine or feminine we are. And I find that the world seems bigger and that I can breathe better in it.

Useful post. I have long felt that the word ‘masculinity’ almost cannot stand on its own any more: the t-word always hovers invisibly behind it, if it isn’t already before it. (That’s just my gut feeling, might be interesting to find a stat on how often the m-word is accompanied by the t-word.)

I found this very helpful and it crystallised some otherwise messy thoughts in my head. I remember when masculinity became a thing about twenty years ago with a series of feminist books rightly pointing out that women can’t be expected to do all the work of rebalancing a gendered society. Men need to change, too. The problem with these structural analyses is when they encounter the reality of men and boys who want to be good people but receive EXTREMELY conflicting cultural messages about what this looks like. It’s also hard for an individual man or boy to feel that they’re carrying the entire weight of ‘the masculine’.